How Heavy Were Iron Age Bows? Part 3

In previous posts I talked about how the bows used for war in Europe and Asia in the 15th and 16th century were much stiffer than hunters or target archers use today. They usually had draw weights on the order of 100-150 pounds, so you could draw the bow to full draw length by tying twine to the string, hanging the twine over a pulley, and hanging a 100-150 pound weight off it. Deer hunters in Canada and the USA tend to use draw weights around 40-70 pounds with traditional bows (compound bows with pulleys are another kettle of fish). Some researchers today invoke the heavy bow hypothesis and argue that bows in the ancient world were as stiff as Chinese, Turkish, and English bows 2000 years later. I am not convinced.

In those previous posts I talked about extant bows which can be reproduced and measured (or sometimes plugged into a physics model- there is a whole PhD thesis just on the physics of archery). Anecdotes about famous shots or feats of arms are a little too subtle for me to discuss in a blog post, and the surviving treatises on archery date to the sixth century CE and later so are past the period I focus on. But there is one other type of evidence!

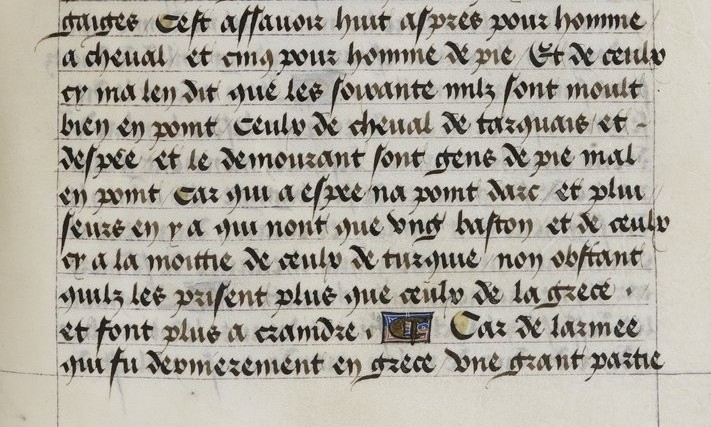

Hundreds of bows survive from the ancient world, but almost all are from Bronze Age Egypt. But thousands of detailed sculptures and vase paintings show archers drawing their bows in almost every society with cities. Many of these were made for kings who took pride in their skills as archers. And skilled workers like sculptors and painters were the backbone of archer militias around the world. While in ‘primitive’ societies every man can be a bowman, in agrarian societies many men were to poor to afford a bow and arrows or too malnourished to draw a strong bow. Militias in England and the Turkish world contained men whose only weapons were a knife and a cudgel or staff.1 Archery was not as expensive as gunnery, because you can use the same arrow many times and most of what you need is made from plants and animals not lead or sulphur, but eventually the arrow snaps or is lost and the bow breaks or just becomes too cracked and dented to trust. You needed to continually put in time and money to be an effective archer. The people with that time and money were the people who carved archers, painted archers, or ordered people to carve and paint archers. Archery was not just a game, it was one of the key acts by which rulers justified their authority. So every ancient sculpture of an archer is trying to teach us something, even if we have to look closely and be patient as we try to understand.

These Assyrian sculptures were not like a comic-book artist today drawing an archer for people who know nothing of archery and getting things wrong. They were more like a small-town journalist in the 20th century drawing a hockey player: something they and their audience saw regularly, participated in, and cared about.

The relief above comes from the time of Assurnasirpal II or Shalmaneser III in the 9th century BCE. It shows a two-man, three-horse chariot hunting Asiatic lions, which used to live in Syria and Iraq but are now confined to reserves in Gujarat, India because the hunters got a bit too effective. The artists have showed many details such as the bracer on the archer’s left arm to stop the string from bruising his skin. He seems to rest the arrow on the side of his hand, like a modern Olympic archer, not on his thumb. The draw is long even though his bow is short, and he holds a second arrow in his draw hand so he can quickly put it to the string. The arrows have narrow fletchings which makes it easier to carry many in a quiver without the feathers getting entangled or crushing each other.

If you learned archery in Canada or Europe, you probably learned to draw the string with three fingers hooked over the string, two below the arrow and one above. That is clearly not what our Assyrian archer is doing. We can see four fingers dangling loose.

About 150 years ago, an Englishman named Edward S. Morse went shooting with a Japanese gentleman. He quickly noticed some surprising things:

My interest in the matter was first aroused by having a Japanese friend shoot with me. Being familiar with the usual rules of shooting as practiced for centuries by the English archers, and not being aware of more than one way of properly handling so simple and primitive a weapon as the bow and arrow, it was somewhat surprising to find that the Japanese practice was in every respect totally unlike ours. To illustrate: in the English practice, the bow must be grasped with the firmness of a smith’s vice; in the Japanese practice, on the contrary, it is held as lightly as possible ; in both cases, however, it is held vertically, but in the English method the arrow rests on the left of the bow, while in the Japanese method it is placed on the right. In the English practice a guard of leather must be worn on the inner and lower portion of the arm to receive the impact of the string; in the Japanese practice no arm-guard is required, as by a curious fling or twirl of the bow hand, coincident with the release of the arrow, the bow (which is nearly circular in section) revolves in the hand, so that the string brings up on the outside of the arm where the impact is so light that no protection is needed. In the English method the bow is grasped in the middle, and consequently the arrow is discharged from a point equidistant from its two ends, while the Japanese archer grasps the bow near its lower third and discharges the arrow from this point. This altogether unique method, so far as I am aware, probably arose from the custom of the archers in feudal times shooting in a kneeling posture from behind thick wooden shields which rested on the ground. While all these features above mentioned are quite unlike in the two peoples, these dissimilarities extend to the method of drawing the arrow and releasing it. In the English method the string is drawn with the tips of the first three fingers, the arrow being lightly held between the first and second fingers, the release being effected by simply straightening the forefingers and at the same time drawing the hand back from the string; in the Japanese method of release the string is drawn back by the bent thumb, the forefinger aiding in holding the thumb down on the string, the arrow being held in the crotch at the junction of the thumb and finger.

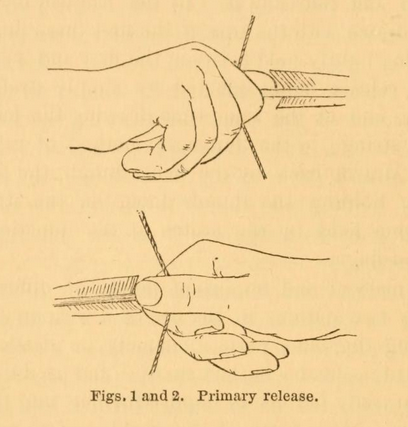

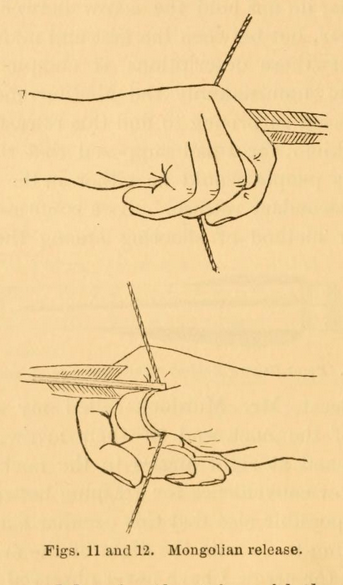

Morse went on to document everything he could find about methods of drawing the bow, visiting embassies, speaking to members of indigenous nations, collecting photographs and writing to contacts around the world. His book is a joy to read because it is full of the best Victorian scholarship driven by pure scientific curiosity and a realization that he could be the first person to answer a question in writing. He gave the world the names for five ways of drawing the bow, namely primary, secondary, tertiary, Mediterranean, and Mongolian. One of the most educational parts of the world of martial arts is learning that everyone disagrees about everything but almost everyone tells you that their way is the ONE TRUE WAY (Herodotus teaches the same lesson, but some people learn better in person). As we just read, Morse rejected one-true-wayism at the beginning of his study, because he met an archer he respected who did things differently but got good results.

The sculpture seems to be showing what Morse called the primary release, where you pinch the arrow against your pointer finger with your thumb. This is the way that most children around the world try to shoot if you give them a bow and arrow. It works best if the nocks are knobbed or ridged to help your finger grip the arrow. It does not work well with a heavy bow, but does work well for quick snap shots where the arrow is released the instant it reaches full draw.

Its also possible that the relief shows a form of the Mongolian release, where the thumb is hooked around the string and the pointer finger holds it in place. The Mongolian release was the ordinary release in recent times by peoples influenced by Eurasian steppes nomads such as Ottomans, Han, and Japanese. Archers who use the Mongolian release usually wear a broad ring on their thumb to take the weight and smooth the movement of the string as they loose. These are not common in ancient sites from the Near East, even though bone and bronze and hard stones like jade are archaeologically visible. In addition, Assyrian sculptures usually show the arrow on the left side (outside, back-of-hand side) of the bow, whereas archers using the Mongolian release usually shoot on the right side (inside, thumb side). Morse goes through some of the possibilities in his article, which I link below.

A remarkable thing is that in the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians were a nation of archers and not a spear-and-bow nation like Herodotus’ Persians. Sculptures such as the Balawat Gates show Assyrians using bows and arrows and short weapons but never spears and shields. They carried spears on their chariots with axes and swords and quivers of arrows, but lacked dedicated groups of spearmen at that time. The Akkadian term for footsoldier was bowman (LÚPAN = qaštanu). At the Late Bronze Age site of Nuzi, most houses contained a quiver of arrows, but there were just five spearheads, and the thousands of tablets preserved when the city was burned to the ground have few clear references to spears or spearmen or spearmakers.2 So this is a sculpture from a nation which saw the bow as the preeminent weapon, but it does not show the same kind of archery that Turks or Manchus or Scots used in recent times.

One of the beautiful things about archery before the 20th century is that even though a bow and arrows are very simple (two sticks and a piece of string) there were dozens of different ways of using them in war. Some nations loosed in a high arc from several hundred yards away, and others closed in and shot flat and level. Some pulled stiff bows, and others tried to shoot as fast as possible. Some used a long draw and others used short. Some massed their archers together and released hails of arrows, while others scattered a few archers among the shield-bearers. Some spread out and ducked and dodged incoming darts, while others packed together behind shields or barricades. Some used the bow for both war and hunting, while in others an aristocrat who shot game with a bow would never dream of going to war with such a humble weapon. There were ingenious devices like the arrow guide (Persian nāwak, Greek σωλενάριον) to let an archer take a long draw with a short light arrow so he didn’t have to chose between carrying many arrows and taking a powerful accurate shot. There were clever tricks like shooting almost vertically to drop arrows on the enemy above their shields or behind a barricade. An archer who wants to shoot many arrows one after another cannot shoot a very heavy bow, while an archer who wants to pierce shields or armour cannot shoot a very light bow. This is a notable contrast to early firearms, where Catholics, Protestants, Ottomans, Chinese, and Japanese all figured out that fire by countermarch was the best way to use large numbers of matchlocks, and everyone with flintlocks agreed that firing two or three ranks at a time from one end of the line to the other was the best way to use large numbers of flintlock muskets. By 1776, tiny variants like giving a file as much as a yard and a half of width to stand in and making them move at a trot were seen as shocking innovations, and they worked best in rather small battles.3

Ancient historians have hardly begun to explore the possibilities. I know of only one article on the mechanics of ancient skirmishing, by Adam Anders, whereas there are dozens on Greek hoplite combat. Bret Devereaux’ post on why archers probably didn’t shoot volleys is the only academic treatment of the subject I have read. And there are many nuances in the art, from the multiple draws shown in ancient Greek vase paintings, to Assyrian reliefs where archers facing left seem to draw differently than archers facing right.

Ten years ago I posted about Roman archery in response to a viral video by Lars Andersen. Everything he does except perhaps the parcour is documented in texts and art around the world, although some of his ways of doing those things may not be the exact way ancient archers did them. There certainly were standing long-ranged archers, whether English archers shooing at butts several hundred yards away, or Bohemian crossbowmen taking aim from behind a pavise shield, but there were many other kinds of archery on ancient and medieval battlefields. But this is not the book on ancient archery which I hope to write one day. So lets turn back to draw weights and round off this post.

As far as I know, archers who draw heavy bows (more than 100 pounds of draw weight) all use either the Mediterranean three-finger draw or the Mongol thumb draw. Those are two excellent ways of drawing the bow, and some historical treatises recommend learning both, just like they recommend practicing shooting with either hand and practicing drawing sometimes to the earlobe, other times to the jaw, and other times to the shoulder. I don’t know any heavy-bow archer today who uses anything but the Mediterranean or the Mongolian draw, because drawing a heavy bow is an extreme physical feat and there are only a few ways to do it that don’t risk physical injury. Onetime commentator Ryddragyn (warning: YT) found Papuan archers who use something called the tertiary release with unfletched arrows and self bows but their draw weights are more like 80 or 90 pounds than 100-150, and when he tried the modern bowstring cut his hand (Papuans lacked fibre plants until recently, so their bowstrings were broad and flat). So archers who are using the primary release must be using lighter bows. Philip Henry Blyth estimated that the primary draw works for up to a 40 pound draw, and that seems a reasonable estimate although everything will depend on the archer and the arrow (modern smooth plastic nocks are a bad choice for this draw but filing lines onto them might help, or 3d printers could create nocks that give more purchase to the fingertips).4

Many ancient paintings and sculptures seem to show the primary release, and hunters in some parts of the world were still using it in the 19th century. So this cannot be dismissed as just an artistic convention because we have ethnographic parallels. Ancient Egyptian art shows archers with composite bows using different draws than archers with self bows (wooden bows).

Before we part, I would like to bring in one more piece of evidence. Lets have a look at the dying lion in the bottom of the relief.

This lion is having a bad day. But notice that he has three arrows in him and is still mostly alive. Today its common for an arrow to pass through a deer and continue out the other side (pass-through). Most bow hunters don’t use heavy bows, but they shoot at close quarters like the lion hunters in the relief. Today Asiatic lions are similar in weight to North American deer although everything depends on the sex of the animal and the specific animal. So these lions should be about as resistant to arrows as a deer. And the sculptor does not seem to think that one arrow will reliably kill. A local police officer recently needed four rounds from an AR to finish off a deer that had been hit by a car, and perhaps the Assyrians believed that “there is no overkill, there is just ‘open fire’ and ‘time to reload.'”

Showing the arrows stuck into the lion could be an artistic convention like the modern TV shows and movie artists which show arrows sticking into targets instead of passing through and disappearing (and show arrows penetrating all kinds of armour instead of bouncing off or getting stuck before they hit flesh). I can’t think of any film or TV show in which an arrow passes through someone and keeps going, from Wishbone on Joan of Arc to the latest big-budget movie. Scott Manning whom I mentioned in an earlier post has an academic paper on comic books where characters get peppered with arrows like St Sebastian or St Edmund because its a striking visual motif. But needing three arrows to kill and failing to send them all the way through is certainly consistent with relatively light draw weights in Assyria in the 9th century BCE.

While many sport archers were reluctant to learn that soldiers in 15th-16th century Eurasia used very heavy bows, its wrong to overcorrect and assume that therefore all bows for war in all cultures and all periods had heavy draw weights. Neither art nor surviving bows supports this. One-true-wayism is always a mistake.

Financial storms are coming like arrows in a Scythian battle. Unlike most Internet writers these days I don’t have a spouse or a salaried job subsidizing my time. If you can, please support this site on Patreon or elsewhere. I touch on things of interest to many different communities, so sharing with friends and colleagues helps too! People are much more likely to acknowledge something if it comes from someone they know.

Further Reading

Anders, Adam (2015) “The ‘Face of Roman Skirmishing’.” Historia 64.3 pp. 263–300

Spyros Bakas, “The shooting methods of the archers of the Ancient Greek World 1400 BC – 400 BC,” unpublished conference paper (2014) https://www.academia.edu/9973149/The_shooting_methods_of_the_archers_of_the_Ancient_Greek_World_1400_BC_400_BC

Edward S. Morse, “Ancient and Modern Methods of Arrow-Release,” Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol. XVII, Oct-Dec 1885, pp. 1-56 https://archive.org/details/ancientmodernmet00mors/

Morse, Edward S. (1922) Additional Notes on Arrow Release (Peabody Museum: Salem, MA, 1922) https://archive.org/details/arrowradditional00morsrich/ (full of data but less joyful than the original, Morse had fallen in with ethnographers who taught him about higher and lower savages and the important connections between the hill-folk of India and the Caucasian cousins; said to have been first published in the Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft fur Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte for 1891)

Kooi B.W. (1983) On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow. PhD thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. https://www.bio.vu.nl/thb/users/kooi/ (this page also has other publications by the author, who has provided consultation services for archaeologists and bowyers)

Szudy, Matthew Jamie (2015) Archery Equipment in the Neo-Assyrian Period. PhD thesis, Universitä Wien. https://utheses.univie.ac.at/detail/33864 (focus on arrowheads)

Faris and Elmer’s Arab Archery (1945) https://www.archerylibrary.com/books/faris-elmer/arab-archery/

Latham and Paterson’s Saracen Archery (1970) https://archive.org/details/latham-paterson-saracen-archery/ Page xxv discusses the use of either Mediterranean or Mongolian draws with heavy bows.

Edward McEwen, “Persian Archery Texts: Chapter Eleven of Fakhr-i Mudabbir’s Adab al-Harb (Early Thirteenth Century),” Islamic Quarterly 18 (1974) pp. 76-99 https://www.proquest.com/docview/1304274762/ (more a collection of anecdotes than a treatise, but glorious)

Gao Ying, The Way of Archery: A 1637 Chinese Military Training Manual, tr. Jie Tian and Justin Ma (Schiffer Publishing, 2015) https://www.thewayofarchery.com/book.html

The Bow vs. Musket blog has many anecdotes about archery after the introduction of portable firearms https://bowvsmusket.com/

Anonymous peri Toxeias (an English translation is in the mail to compliment the Greek text and German and Italian translation which I already have)

Iliad 4.122-123 and Procopius on drawing to the breast or the nipple rather than the ear or the jaw

Edit 2025-05-22: I am told that Kim Han-Min dir., War of the Arrrows (2011) has a scene where an arrow goes through one warrior and kills another behind him

(scheduled 12 May 2025, revised 15 May)

- The English militia laws and rolls are published many places (I will talk about one in “Linen Armour in the Frankish Countries, Part 2”), while the Ottoman raiders are in Oman’s Art of War in the Middle Ages, volume 2 page 347 (he cites Bertrandon de la Broquière, a very interesting character). Europeans who faced Turks from the First Crusade to the 15th century noticed that ordinary Turkish shepherds just had a bow and a knife or club, while rich men had swords or lances and sometimes even helmets and armour. As late as 1813, the Czar’s Central Asian levies had just horses, bows, and arrows but no swords or lances (this source’s eyewitness description of fighting Turks could have been written any time in the previous 700 years). ↩︎

- Timothy Kendall, Warfare and Military Matters in the Nuzi Tablets (PhD Dissertation, Brandeis University, 1974) pp. 250, 251 ↩︎

- Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2010) which I have not read and Mark Urban, Fusiliers: The Saga of a British Redcoat Regiment in the American Revolution (faber & faber: London, 2007), pp. 66-69 which I have. ↩︎

- Blyth, The Effectiveness of Greek Armour Against Arrows, p. 62 ↩︎

Interesting to read about Morse. I’ll have to give his paper a read, because it sounds like a fun and informative one.

FWIW, David Nicolle has mentioned Islamic bows found alongside armour from the 13th of 14th century that he says looked to be surprisingly weak, but unfortunately while C14 dated to the period, they were likely looted and the private collector isn’t likely to let him provide more information than what he already has. I can try and dig out the exact reference, if you want, but it sounds like the draw weights from the two Islamic archery manuals that have been translated into English are for military shooting as well as target practice.

Also interesting to hear about the Neo-Assyrians being so heavily archery focused. I would have thought they were much bigger on combined arms.

For the century after Shalmaneser we don’t have many detailed sources, but it seems to have been during Sargon II’s wars with Sarduri and Rusa of Urartu that the Assyrians grudgingly acknowledged “maybe the (Neo-)Hitites and Urarteans have something to this idea that shields are not just for sieges.” 300 years after that Herodotus thought that the Assyrians were a spear-and-shield nation.

It also seems that Turkish bows in the 18th century were less stiff than Karpowicz’ estimate for earlier Ottoman bows in the Topkapi Palace. I don’t know if the distinction in research between “flight bows and war bows” is any more real than the distinction between “longbows and warbows” (AFAIK, there were people in the UK shooting medium-weight bows, sometimes with thickened middles and other 19th/20th- century features, and they called their bows longbows, so the people who wanted Mary Rose bows picked a new name).

I believe Neo-Assyrian bows had draw weight 16-40 kg, we don’t know what kind of bows had Kassites https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kassite_dynasty From the sources we can assume Elamite bows were better, Neo-Hittite bows are implying (reliefs) with their shape, and presence of archer glove that these are heavy bows. I want to publish something about Neo-Assyrian army soon. I believe in era 934-745 BC chariots, archers had big role in open battles. In era 745-605 BC Neo-Assyrian armies had big numbers of archers (primary sources), yet spearmen are more numerous, armoured. Spearmen are striking force, archers their support.

My hypothesis is that Cimmerians, Scythians brought new class of weapon (You know recent lecture and debate panel with Shelby and others on YT, links are somewhere in my old emails). This composite bow had layers of materials, wood, glue, horn, silk, laquere paint. Strength of such bow is 55-70 kg or even more (with thimble and training even noob like me can train himself during few weeks in summer camp! My true story, last time I have used modern sport bow as 12-years old. 14 years later I trained on Medieval longbow, so my previous knack on archery is hardly experience). Thimbles existed in various forms, Mycenaean Greeks, Nubians, Scythian cultures, Chinese Warring states, Han dynasty, etc.). Previously many academics thought Eastern Scythians (Xinjiang finds) had layered composite bows, Western Scythians (Ukraine) had only laminated weaker bows. Yet I (and some historians, bowyers disagree), additional proofs like short arrows = weak bows are not viable. Crimean Tatars had short bows, arrows and they were strong as Turkish ones. Russian speaking can read https://dariocaballeros.blogspot.com/2020/09/the-army-of-crimean-khanate-libre.html

War of the Arrows (2011) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2025526/ was my favourite movie from that year. You can check my work about overview of Asian cinema since 2009 here https://akicon.cz/ section archiv proof instead of promise:) Year 2011 https://akicon.cz/static/data/2011/Novinky_asie_2011.pdf Koreans have many movies/tv series with quite realistic flair of using Medieval weapons. I have to consult my book https://www.amazon.com/Muye-Dobo-Tongji-Comprehensive-Illustrated/dp/1880336537 about power of Korean bows, also my Chinese sources for era 16th-19th century. I have to recommend documentary about arrow production https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ga27AO_306o How is reed comparable as material for the arrows contra to bamboo, is it easier or the same? My expertise lies in arrowheads production, not in arrowshafts and rest of elements.

I am starting to think that what Grozer and his competitors market as an Assyrian bow might be more of a Chaldean or Elamite bow because of the curved arms and recurved tips. Compare Ashurnasirpal II’s angular composite bow (like the NK Egyptians used) with these Chaldean bows from the reign of Ashurbanipal. I wonder when and where bows with recurved tips appear? Hope to get in touch with Grozer in the near future to learn what inspired that model.

Energy is work and W = F⋅d so only drawing a bow 24″ rather than 28-30″ significantly reduces the energy it stores. Latin crossbows had that problem (bowyers in the House of Islam mounted proper composite bows with long draws on stocks, and I think Chinese crossbows were similar).

“No arrow travels further and is lighter and works better than one of reed (Persian kilk), but it needs to be well matured and dried and driven through a mould and straightened.” – Fakhr-i Mudabbir (see commentary on pages 93 and 94)

He does not seem aware of arrows of dense woods like ash or beech. The French treatise on archery printed in 1515 says that arrows of ash are good for testing armour. From a physics standpoint, a reed arrow will be light for its length and diameter (and many ancient arrows had narrow sockets, so the shaft will bend or break easier than a heavier arrow).

Some of the Arabic and Persian treatises are explicit that you do not want to use a heavy bow for feats like shooting a handful of arrows one after another.

Attitudes to draw weights are strange. Armin Hirmer who teaches Asiatic archery and reviews bows on YouTube seems to mostly use light bows (a 35# at 28″ drawn a bit longer than that caused some muscle strain because he had been focused on getting ready for the video and had not taken a moment to warm up; he is not young and lots of archers use lighter bows as they age). Its not hard to find people on the Internet pronouncing “50# is extremely heavy” when its about the minimum for taking medium-sized game and most healthy men can learn to shoot a bow like that with moderate practice. With compound bows and all the doohickeys that people will sell you these days, it seems like it would take some talking around to find someone who was on the same page!

Life is triage and an archer who focuses on drawing monster bows is not training to shoot very fast or almost vertically or at moving targets or any of the other excellent skills an archer could learn for war or hunting. Most modern archers seem to focus on skills other than drawing heavy bows, because deer and turkeys don’t shoot back or wear lamellar. A Brit I talked to says that many “English warbow” archers just try to shoot the beefiest bow they can and don’t necessarily learn to hit anything with it or shoot fast or any other useful skills. And we have sources back to the 15th century of soldiers mooning archers or gunners who did not seem to be able to hit a target.

Blyth goes into the pros and cons of different Mediterranean reeds for arrows (Phragmites australis, Erianthus Ravennae, Arundo Plinii).

Weren’t most Western Turkish bows short, like 105-120 cm from nock to nock? And they often shot 25″ arrows with an arrow guide, maximum about 29″ long