What Ridley Scott’s “Gladiator” Gets Right

In the Kingdom of Khauran, every hundred years a witch shall be born to the royal family. In the United States of America, every ten years Ridley Scott shall borrow unimaginable sums of money to mangle a new period of warfare. This has been foretold and has come to pass although none can foretell whether he will return with an Amarna Age epic where the chariots have exhaust pipes or a science fiction adventure which makes Starship Troopers look like sound military science.1 Making fun of all the things these films get wrong is healthy fun around a gaming table or along a bar, and recently Bret Devereaux entered the genre on his ACOUP blog (part 1) (part 2) (part 3). But as I wrote back in 2016, complaining about bad things is often bad strategy. So this week I will wrote about the things I like about the opening scene in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator. That is something I can cover in a short bookandsword post, whereas it takes three long ACOUP posts to cover some of the things that are wrong with the same scene.

Two Armies Unlike in Dignity

Ridley Scott’s ideas about Rome were confused at best, but he did get it into his head that he wanted to portray a battle between the material-rich army of a complex, unequal society and the material-poor army of a simple, equal society. Many of Rome’s northern neighbours did not have large settlements, spectacular monuments, or gorgeous works of art. Some did not even have swords like their Iron Age ancestors.2 Since they were in contact with the La Tène ‘Celtic’ world and the Romans, these were almost certainly deliberate choices by people who had seen that if you allow too much difference, some people will start to take more than their fair share, change the rules so you can’t say no, and tell you that they deserve it because they are special. If every man is a warrior, they have to use weapons that every man can obtain, and use them in a way they can learn between producing food, building homes, and raising their children. The Hjortspring people certainly knew about bows and arrows, but they did not bring them to war, probably because there was a custom against this or because it was hard for a slash-and-burn farmer to find the time to become a really good archer.

Meanwhile the Romans had lost control of their elite during the Republic. More and more wealth had become concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, and institutions and practices of self-government had shrunk and faded. By the second century CE Italy was as rich in material goods as eighteenth-century Europe but as politically primitive as the Montreal mob. The Romans had a society where someone could do nothing but put feathers on arrows for a living, but also a society where people with a new cloak every day lived next to people who got a new cloak every two years. If the Roman army needed a skill, it could hire people and pay soldiers to learn it; if it needed a piece of equipment, it could make it or buy it. If necessary, it could find soldiers with the right skills in Syria and send them to Britannia where they left Aramaic inscriptions on their days off.3 So Roman armies and barbarian armies were starkly different in the second century CE.

Scott’s Roman army consists of legionaries, archers, cavalry, and catapults who all have different roles. The archers and catapults pelt the woods with fire arrows and pots of burning oil, then the legions advance, then finally the cavalry charge the barbarians in the rear. In contrast, the barbarian army consists of a mass of men with spears, swords, and axes. They have different weapons and shield, but all beat their weapons on their shields, then back away from the Roman missiles, then charge the Roman legions in a loose pack. Barbarians with long spears and long axes don’t work from the protection of men with shields and short weapons. In one sequence of shots, the barbarians have a few archers with wooden bows who shoot a single volley at the Romans at close range. That is the only time where one group of barbarians fights differently than another.

All of Scott’s Romans except a few flunkies are armoured and have helmets. Fun-ruining historians have long suspected that neither the Roman legions or the Assyrian royal corps really managed to give every man metal body armour, but sculptors and film directors pretended that they did. In contrast, none of the barbarians seems to have any metal armour at all. They wear random furs and leathers with studs and stiff hats which we might be supposed to understand as protective, but no embossed breastplates, coats of mail, or segmented shoulder guards. Their only protection is their shields, and since its a Hollywood battle, towards the end everyone loses their shield anyways.

I have written about how Scott gifted the world of film with the desaturated blue-grey battle scene which is an evil which will live after him like Ignatius Donnelly’s writings. Armies before the 20th century went to war in the brightest, most sparkly things they could beg, borrow, or steal, because if you were not willing to risk things, how could anyone trust you to risk your life? Going to war in your best showed that you had access to resources, and it increased the chance that people would recognize you as you did something heroic, and being a war hero could change your life. As Baldassare Castiglione teaches us, you have to be seen and recognized doing something to get the credit.

But Scott used this visual device to tell a story about the two armies. Everything that his barbarians carry is black, blue, brown, and grey. His Romans have yellow brass and embroidery, red flags and cloaks, and white feathers on their arrows. The brass on their armour is sometimes even shiny, whereas the only shiny thing that any of the barbarians wears is the barbarian leader’s belt buckle. Maximus’ horse wears more bling on its head than the wealthiest of the barbarians wears on his whole body.

The Roman fieldworks with wooden stakes and mantlet shields are confusing since the Romans want to attack and want the Germans to stand and fight (and the Romans have an overwhelming advantage in firepower and are sitting atop a hill). But they at least add to the impression that the Romans have endless stuff, bulky, martial, intimidating stuff.

The opening battle scene reminds me of Tacitus on the barbarians. Tacitus was aware of some of the differences between Romans and northern barbarians in general, but neither knew or cared the details. He was much more interested in moralizing and presenting binary oppositions where the barbarians were the anti-Romans. If you look at this scene as a rich British person imagining what a battle between imperial troops and barbarian might have been like, like Tacitus imagined what a battle between Romans and barbarians might have been like, its easier to enjoy. Scott fills his film with tropes from Hollywood war movies and Hollywood chatter about war, but Tacitus filled his writings with tropes from Latin literature and senatorial chatter about the Good Old Days and the Leitmotif of all Roman literature, “are we the baddies?” Neither was a good Rankean who just wanted to establish what had actually happened and leave the moralizing to the lazy.

Catapults

One of the most unusual practices of the Roman army was that they used stone-throwing and bolt-throwing catapults in the field. Alexander and his successors, to my knowledge, are never said to do this. Onomarchus of Phocis ambushed Philip’s army with stone-throwers who were probably men with rocks. Philip, Alexander, and the successors used catapults in sieges and river crossings but not skirmishes or battles. Examples after the Roman empire are also scarce: the French once used some catapults against Flemings drawn up in a strong position, and the Flemings came out, chopped up the ropes, and returned to their own lines leaving the ruined engines behind them.4 Catapults were just not so destructive or long-ranged to be worth the trouble of setting them up and adding the complexity of another weapons system.

The Romans created a myth that only they knew how to build siege engines or besiege cities. Like many myths this was created to be unfalsifiable, because if the Romans hear of barbarians using siege engines, they declared that the barbarians had stolen them from the Romans or been trained by Roman deserters. The sculptors of Trajan’s Column lingered on depictions of Roman catapults and Dacian forts being methodically stormed. So I appreciate that Ridley Scott found an excuse to show Roman catapults pelting the barbarians, even if he had to combine it with the FIRE ARROWS! trope.

Barbarians from Central Casting

Ridley Scott’s barbarians are generic Hollywood barbarians, with tunics and trousers, swords and shields, axes and carnyx trumpets and lots of fur and brown leather. You could drop the same extras into the recent Netflix Vikings show without making them switch costumes. That also reflects how sculptors at Rome portrayed the barbarians during the Roman empire. It is extremely hard to tell whether barbarians in Roman art are supposed to be Germanic, Sarmatian, Dacian, or Parthian because they are all given the same sort of clothing and equipment. Sculptors in the provinces give detailed pictures of local fashions on cheap local stone, but sculptors in the capital take the finest imported marble, say “barbarians have wild hair and trousers and exotic shields and no armour,” and start carving. Just like Ridley Scott, they did not know or care about the details of specific nations at specific times, and certainly not practical details like “is that a centregrip shield or a strapped shield?” Even specialists are confused by Parthian art that shows men with Parthian trouser-suits but European spined oval shields.5

Some of the Romans wear Superman cloaks fastened by two pins on the two shoulders. Of course that is not how you wear a cloak to keep yourself warm and dry and un-sunburned, but it probably helped some viewers understand that Maximus’ soldiers were the good guys. Giving all the Roman legionaries segmented armour and all the Roman archers coats of mail also helped viewers recognize the different types of soldier.

The battle was filmed at a softwood lumber plantation at Bourne Wood in England. This is not a good representation of Roman Germania with its dense network of small farmsteads separated by working woods, but it is the world of forests which Romans imagined when they imagined the edges of the world. Everyone in Rome knew that on the edges of their world were bogs and forests and mountains and killing heat or chilling cold, and they did not bother to double-check with the merchants who traveled north to trade Roman iron and wine for barbarian amber and slaves.

The Battle Piece as Rag Rug

In many ways, the battle scene feels like Scott threw together a bunch of clips. First there is the bombardment of the woods with fire arrows and jars of burning oil, then the Roman legions advance, then the barbarians loose a volley of arrows and charge, then the Roman and barbarian infantry lines come together, then the Roman cavalry ride through the woods, then some of the barbarians in the rear of the barbarian army turn to face them, then there is chaotic single combat, then there is a panorama over the burning battlefield with the dead and wounded. Its not always clear how you get from one to the other and there are some editing errors like a scene where the barbarians advance over ground feathered with arrows before the Romans draw their bows. Its hard to understand why in the first shot of the barbarians, all the barbarians have swords and axes to wave in the air and beat on their shields, while when the barbarians charge, many have spears, even though safety officers are worried about extras falling and impaling each other or tripping over each other’s spears.

If you have never fought in a group, go try your local boffer-fighting club, because you will see why breaking formation quickly leads to everyone being dead, while just two or three people are much more effective as long as they cover each other and nobody can get behind them. As long as you keep on your feet and don’t get hit you can have fun whacking away at people who are distracted or make beginner’s errors like letting their shield move out of position as they wind up to cut. And of course losing your helmet or your shield is a very bad idea even if it makes it easier for the camera to see your face. However, this type of battle scene reminds me of ancient art.

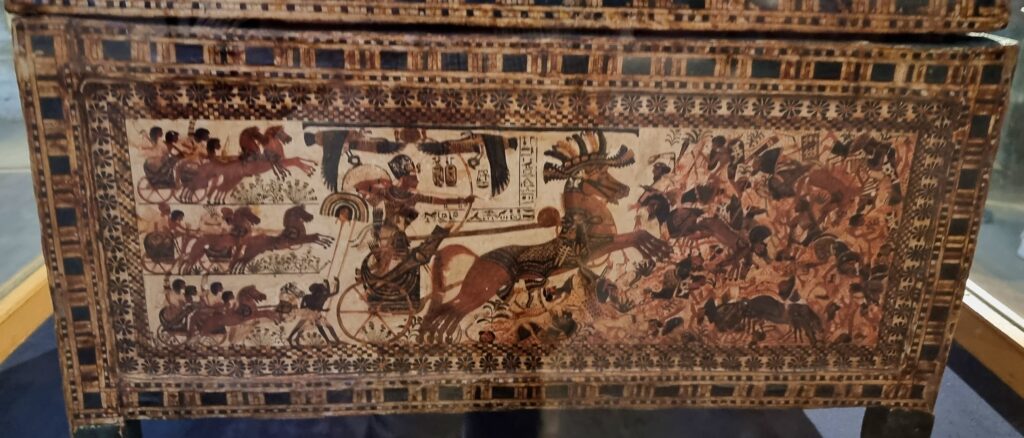

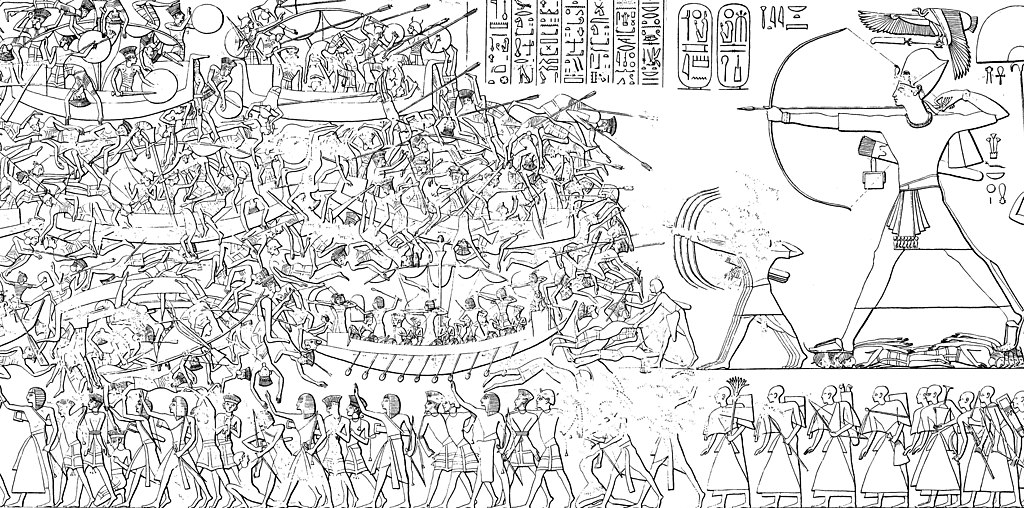

Ancient art west of China often depicted battlefields as filled with chaotic bodies fighting and dying. Civilized and organized peoples like the Egyptians and Assyrians often showed groups of two to four soldiers pushing their way through the enemy mob, while disorderly peoples like the Greeks who could barely line up and charge together focused on individuals pulling each other’s hair and stabbing each other. Almost the whole space was filled with bodies, with no voids when the two sides decided they were quite close enough and getting closer would be too dangerous. The battle-picture-as-diagram with blocks of little figures holding little weapons only appears in Europe in the sixteenth century. I hope one day to have time to explore why this might be. The “Hollywood melee” is not how people with any experience fight a battle, but it reminds me of the painted battle chest from Tutankhamun’s tomb and the Abdalonymus sarcophagus from Tyre.

The single barbarian volley of arrows also shows why you don’t shoot arrows in volleys. When they see the barbarians nocking their arrows the Romans crouch down behind their shields and hold their shields overhead like a Late Roman foulkon. After the arrows have landed they get up to fight. The Zulu figured out how to deal with British artillery in the same way, throwing themselves to the ground when the gunner got ready to pull the lanyard then getting up after the shell exploded.7 A later Roman military manual says that European barbarians make beginner’s errors like failing to post flank guards, so this shot at least shows the barbarians trying something which the Romans defeat with training and equipment.

In the days of the open web, medievalists Paul Halsall and Steve Muhlberger had some thoughts on how to talk about historical films which are subtly different from mine. Halsall noticed that Scott avoids the trope of the “early Christian” from sword-and-sandals films. If you want a take by a historian which is different from my take and Bret Devereaux’s take it is well worth exploring.

Matthew Amt’s Law

The most important things to know about ancient films and TV shows is Matthew Amt’s Law: assume everything you see on a screen is wrong! The power of fiction is so great that if you don’t deliberately chose to put it aside fiction will colour how you think about the past. In the second half of a long and violent life, Marc MacYoung had given up watching action and war films to focus on romantic comedies because most screenwriters have some experience with romance. I never felt a desire to watch this film a second time because it has some spectacular set pieces but is not very good as a story or a period piece. It is meant to make you feel, not think. Russel Crowe’s story that they started with just 32 pages of script and had to improvise many lines and even character names during shooting seems plausible.

But if you enjoy Gladiator as something like Trajan’s Column or the res gestae divi Augusti, not the Darius Mosaic or Xenophon’s Anabasis, I think you can have fun watching it once. It does not show how things were back in the day, but it shows the way that wealthy people in distant cities imagine battles between their army and barbarians. And these days, there are all kinds of small-budget films by people who care about the details of the past. Big-budget films are not made for us, but we can use our modest resources and make things that fill our own needs.

This will be my last regularly scheduled blog post of the summer. I have bike rides to take, a book to send in, shields to paint, and a better job to find, and in the current state of the world good honest writing takes an immense amount of time and energy indoors behind a computer. If you want me to keep blogging, please support this site.

Edit 2025-07-27: trackback from Hacker News https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=44686049

(drafted 13 July 2025, completed 29 July)

- “Verhoeven’s or Heinlein’s?” Starship Troopers the film shows an army which could be outfought by a troop of Girl Guides, but Heinlein wrote his novel after parachuting had become too dangerous to risk against anyone other than a low-level insurgency (Marc R. Devore, When Failure Thrives, The Army Press, 2015), and Mobile Infantry bouncing into the air seem awfully vulnerable to anything on the battlefield that can shoot. Fun-ruining fans are also worried about power armour falling through floors or getting stuck in doorways. Veteran wargamer (and fellow British Columbian) David Pulver gives a brief overview of the problems in GURPS Classic Mecha (1999). Pointers to the pop military mechanics that inspired Starship Troopers, like H. Beam Piper got his contragrav cavalry from speculations about helicopter gunships, would be appreciated! ↩︎

- An excellent introduction is Jørgensen, L. / Storgaard, B. / Gebaue Thomsen, L. (2003) The Spoils of Victory: The North in the Shadow of the Roman Empire (Copenhagen) ↩︎

- Rather than an academic paper how about some local news: Andrew White, “South Shields tombstone is to be loaned to British Museum,” The Northern Echo, 28 January 2024 ↩︎

- The battle of Mons-en-Pévèle on 18 August 1304: J.F. Verbruggen, The Art of War in Western Europe During the Middle Ages, second edition (The Boydell Press: Woodbridge, 1997) p. 199 (I can’t find my copy of Kelly DeVries’ book on these wars). ↩︎

- Michael J. Taylor, “Celtic Military Equipment in the Ancient Mediterranean: Innovation, Imitation, and Empire, 400–25 BCE,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 87 No. 3 (2023) p. 595 (one of the two is London, British Museum, Museum number 1929,1012.356) ↩︎

- W. Raymond Johnson, “An Asiatic battle scene of Tutankhamun from Thebes: a late Amarna antecedant of the Ramesside battle-narrative tradition,” PhD Thesis, University of Chicago, 1992. Johnson retired in 2022 so he may or may not get around to finishing a book based on his thesis. Academia is a strange world, and wealthy American research universities are even stranger. ↩︎

- The best source I can do for this is Charles Aikenhead, “Isandlwana and a Four-Letter Word,” Military History Journal (The South African Military History Society / Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging), Vol. 18 No. 2 (June 2018) http://samilitaryhistory.org/jnl2/vol182ca.html ↩︎